Iowan more than a footnote in JFK lore

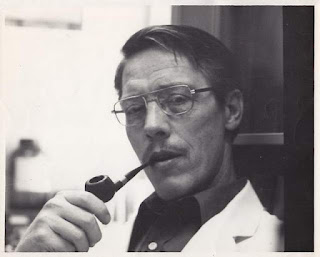

Earl Rose was the medical examiner in Dallas in 1963 when

President John F. Kennedy was shot and killed there.

This photo was taken in the mid-1960s.

Written by Kyle Munson

The Indianapolis Star

April 29, 2012

The world tends to remember 85-year-old Earl Rose, a retired forensic pathologist and University of Iowa professor now facing his own final days, for one fleeting moment in the middle of a national tragedy.

He’s lived in Iowa City since 1968, but the day in question was five years earlier down in Texas — Nov. 22, 1963.

A New Yorker article earlier this month recalled in vivid detail how President John F. Kennedy was shot and killed in downtown Dallas. Lyndon Johnson took the presidential oath that day in Air Force One’s crowded stateroom while the jet was parked on the tarmac:

“Kennedy’s aides had been able to remove the dead president’s coffin from the hospital only after an angry confrontation with the Dallas County medical examiner, who, insisting that an autopsy had to be performed first, had stood in a hospital doorway to block them, backed by policemen. They had literally shoved the examiner aside to get out of the building. …”

The medical examiner was Rose, then 37, back when he preferred a pipe clenched between his teeth and a daily wardrobe of a crisp white shirt and necktie. He had been hired earlier that year by the city and county of Dallas to establish a scientifically valid medical examiner’s system to replace the lay coroners who also served as elected justices of the peace.

Five months into his new job, the president was assassinated on his turf.

At that time, the murder of a president wasn’t covered under federal law, so Rose’s stance was practical: The president’s autopsy should be conducted immediately under proper authority, with the necessary expertise at hand as well as the emergency room doctors who operated on Kennedy. Crucial evidence could be gathered in pursuit of the then-unknown assassin or assassins.

But Kennedy’s body was whisked out of Dallas. Rose did conduct autopsies on both the police officer who was killed, J.D. Tippit, and later the assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald.

“I remain convinced that the laws should not be suspended for the rich and powerful,” Rose later wrote, “for in the final analysis the laws serve to protect them.”

So there Rose stood in the hospital with Jackie Kennedy, then two days later in the same room with Oswald’s widow, Marina. Rose was called out of church Sunday morning after Jack Ruby gunned down the president’s assassin.

Rose’s role gets reprised with each new surge of attention on the assassination. The New Yorker article was an excerpt of the fourth volume of Robert Caro’s epic biography of President Johnson, “The Passage of Power,” to be published Tuesday.

Next year will mark the assassination’s 50th anniversary — yet another chance to rehash the drama.

Life 'swindling' Rose as his memory fades

But I write this column not just to revisit the Rose connection to history, but to remind Iowans of his full and rich life beyond the footnote in Kennedy lore.

At least it’s fitting that the moment typifies Rose’s rigorous sense of justice.

“I think that he felt a good autopsy usually led to justice,” said his wife, Marilyn, as we sat in her apartment in Iowa City’s Oaknoll retirement home.

A display case of her husband’s cow-bone carvings hung on the wall in the next room — tiny figures of a coyote, cowboy and more, meticulously fashioned from cattle bones gathered from an abattoir near Riverside. Rose also has been a woodworker, and his homemade toys line the shelves.

But Rose wasn’t with us. He’s now under full-time care as he fades in the face of late-onset Parkinson’s and dementia.

“My preliminary reaction to the diagnosis of Parkinson’s mirrored that of Mark Twain who, on the death of his invalid daughter, observed bitterly that ‘She was now set free from the swindle of this life,’ ” he wrote in the wake of his diagnosis in 2005.

“Life is still swindling him,” Marilyn, 84, wryly observed.

Her husband has lost the ability to carry on a conversation, and even his long-term memory evaporated in the last year.

A recent bout with pneumonia nearly proved fatal, and Rose remains bedridden. But the pathologist’s meticulous, agile mind still springs forth in hundreds of pages that he and Marilyn have compiled.

The couple in retirement enrolled in writing courses at the local senior center. Their efforts in 2001 yielded the 266-page “My View of History 1963-1968,” which covers the Kennedy assassination and its aftermath, down to Jack Ruby’s 260-gram spleen (from the autopsy that Rose conducted in 1967).

Lifelong reminiscences followed in 2004 in the 175-page “My Ana” — or “loose scraps.” A couple dozen copies were printed to distribute to the family, as well as to the university library archives. A pair of small addenda followed as Rose slipped further into Parkinson’s, and Marilyn was forced to become more of an active and interpretive editor.

Through poetry, Rose wrote that he discovered “a new joy and pleasure with pleasing harmonies and rhythms that are akin to a heartbeat.”

The poem “My Memory” from December 2007 reflects on his own decline:

“In spite of might and main,

“I cannot recall the thought again.

“It strays far from me.

“The shadow of it leaves no record on my memory.”

But then Rose adds a footnote that betrays both his sense of humor and zest for accuracy: “If I had lost as much memory as this poem implies, I wouldn’t have been able to write it, i.e., I have not yet ‘quietly retired.’ ”

Rose’s practical sensibilities initially were forged as the son of a cowboy and rodeo rider during the Great Depression on a remote ranch in western South Dakota, 26 miles from the nearest town, Eagle Butte. He described it as a land of howling coyotes among the “melange of sage brush, cactus, sandburs, rattlesnakes, gumbo soil and restless winds bearing unceasing movement.”

Rose dropped out of high school in 1944 at the end of his junior year to join the Navy and serve on a 311-foot-long submarine in the South Pacific.

Marilyn grew up a farm girl on the opposite side of the state. The two met when Rose was enrolled at Yankton College, and she was a med tech student at a nearby hospital.

Rose always referred to himself as a “visitor” to the Mennonite faith in which he and Marilyn were wed in 1951. They later joined the local congregation in Iowa City, and together they raised six children.

He worked in private practice in Lemmon, S.D., and as a forensic pathologist in Virginia before the family spent most of the 1960s in Dallas.

The 1967 publication of William Manchester’s “Death of a President,” serialized in Look Magazine, disparaged Rose’s role in the assassination.

He worked on major Iowa forensic cases

So the Roses relocated to Iowa City for anonymity and many other reasons — including the medical school and proximity to family in South Dakota.

Marilyn also enrolled in graduate school for anthropology in 1972 and taught at the university for a couple of decades.

Rose was called in for major forensic cases around Iowa. The Register archives also detail that “the intention was that Rose would become the state medical examiner … but no money was appropriated to run the office.” Another forensic pathologist, a student of Rose’s, finally was appointed state examiner in 1983.

Marilyn said that her husband “felt some of the futility of trying to get it politically moving.”

Rose’s work endures. Frank Mitros, still a pathologist at the university’s Carver College of Medicine who worked alongside Rose, talked about a study set of human hearts that Rose assembled in the 1970s — valuable examples of the anatomy of specific diseases and preserved all these decades with formalin and delicate handling.

The week that Mitros teaches his students with the 30 or so hearts, he typically spins a tale about Rose, who he said offered an uncommon background of medicine, forensics and law. After a conversation with Rose, “I always found myself thinking about things in a different way,” Mitros said.

He believes findings in case were right

Rose took stands throughout his life. In 1995, he spoke out against the death penalty in front of the Iowa Legislature, describing a gruesome electrocution that he witnessed and concluding with the line, “Vengeance is not justice.”

He and Marilyn in retirement worked as mediators for Johnson County in small claims court.

These days, when a young staffer at Oaknoll catches word that Rose somehow was involved in presidential history, Marilyn says, “Why don’t you Google him?”

“Their eyes get very wide,” she said.

Rose kept mostly silent about the Kennedy assassination for decades. But in the wake of Oliver Stone’s outlandish “JFK” in 1991, he granted an interview to the Journal of the American Medical Association for an exhaustive, clinical retrospective.

Kennedy’s autopsy, conducted at Bethesda Naval Hospital in Washington, D.C., by then had come to be seen as flawed and a contributor to rampant conspiracy theories. Rose in his writings remains confident that the president was killed by two bullets fired from behind by Oswald.

He also writes about how he was asked whether the Kennedy death was the worst tragedy he endured.

“I find that the most poignant tragedies are those not involving presidents, statesmen, clergypersons or the rich and famous,” he wrote, “rather the most tragic deaths involve the people who have no reserve of emotional support, many of whom are poor.”

That’s a sense of justice that comes from the everyday, not just Nov. 22, 1963.

Joe, thanks for publishing this item. DSL

ReplyDelete